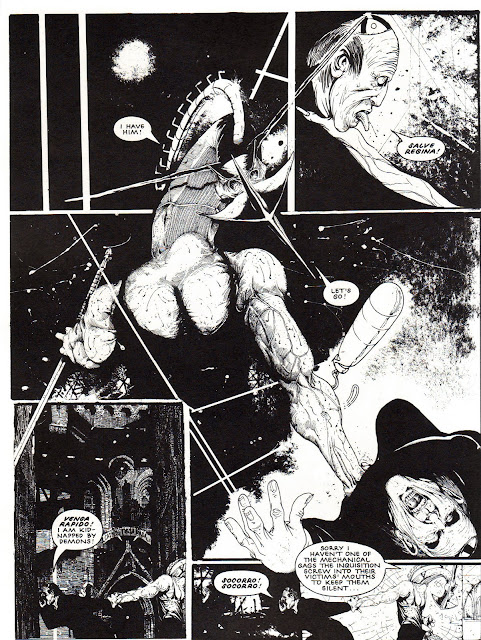

We begin with an image of violence. The page is highly stylized, beautifully rendered, and embroidered with details. Although the image is mannered and exaggerated, there is a solidity to the drawing, a consequential materiality. There is a hardness to these lines, a severity which helps us to believe in the unrelenting cruelty of these villainous figures. In the corner is an illuminated text, grotesque in form, narrating a future perspective of a distant and dark history. We are shown a medieval future that has regressed into violence and dogma, into the worst that history has to offer: Intolerance, unthinking superstition, ignorance, brutality. However, I would like to suggest that the image also introduces an absorbed and reconfigured form of surrealism. It is given a new form within a space of mass culture. A powerful counternarrative within a branch of culture industry aimed at children. It is an uncanny reappearance of subversive and irrational forces that tap into a play of politicised aesthetics. The splash page that introduces Book 1 of Nemesis the Warlock, sets an intense tone that is to continue for the its entire run in the weekly anthology comic 2000AD over the course of the 1980s. 2000AD was a complicated site of escape for young readers. The future generally looked pretty bleak, but perhaps not much worse than the past or present. The origins of 2000AD are linked to the co-creator and writer of Nemesis the Warlock, Pat Mills. He was working in both an editorial and script writing role for the company IPC, who together with rival company D.C. Thomson, dominated the world of British comics in the 1970s. In 1976, prompted by the immanent release of a number of science fiction films, including Star Wars, Mills was instrumental in founding 2000AD and ensuring its initial survival at a time when the lifespan of a comic title was notoriously short. After abandoning his editorial role, he returned to the title as a writer, where he maintained a consistently adversarial and difficult relationship with paper’s management. While it is important to recognise that the commercial potential of science fiction, in the eyes of the publishers of the comic, was connected to the success of cinematic blockbusters, the terrain of science fiction that Mills and other creators responded to was one that had been transformed by the New Wave of British Science Fiction that had emerged from the pages of the magazine New Worlds in 1960s. This was an influence that I’d like to think was not limited to the textual content of the work that emerged from New Worlds, but that was also connected to emergent visual sensibilities.

In 1962, the traditional science fiction illustrations were dropped from the cover, opting instead for photographs of featured authors, and then in 1963 it lost cover images completely.

Under Michael Moorcock, who became editor in 1964, not only was there a shift in the direction that the content took, towards the emerging experimental sensibilities of Aldiss Ballard and others. There was also a new graphic sensibility. By the turn of the 60s, this had further evolved into a form that was sensationalist, while retaining a critical edge that displayed borrowings from Pop and Surrealism.

The visual cultures of science fiction would continue to change. The use of Surrealist images in Britain gave way to a greater synthesis of elements in the generation of new imagery in line with pop-culture tendencies, with a convergence between book covers and album covers.

The diffusion of surrealist tendencies was, of course, part of this broader set of trends. Covers such as this for Ballard’s The Wind from Nowhere, by Alan Aldridge, replaced appropriation with synthesis, modernist surrealism with a 60s graphic sensibility. We can see the emergence of new visual possibilities for science fiction.

In creating the universe of Nemesis the Warlock, Mills and O’Neill tapped into the current of Surrealism than ran through the emerging visual culture of science fiction.Mills also tapped into a current of Surrealism in the pages of the French science fiction comic Metal Hurlant, He saw that audiences can be pushed into expecting more, and demanding more, from comics. First published in 1974, and co-founded by Moebius, Metal Hurlant was a space for experimenting with non linear narratives, while openly obsessed with eroticism, of various degrees of explicitness and weirdness.

In creating the universe of Nemesis the Warlock, Mills and O’Neill tapped into the current of Surrealism than ran through the emerging visual culture of science fiction.Mills also tapped into a current of Surrealism in the pages of the French science fiction comic Metal Hurlant, He saw that audiences can be pushed into expecting more, and demanding more, from comics. First published in 1974, and co-founded by Moebius, Metal Hurlant was a space for experimenting with non linear narratives, while openly obsessed with eroticism, of various degrees of explicitness and weirdness.

It is clear that French comics, and Metal Hurlant in particular had an enormous influence on Mills, that ran parallel in his scripts with his translation of the dark and ambivalent tendencies of the New Wave of British Science Fiction. The roots of Nemesis the Warlock c an be found in the final episodes of the series Ro-Busters. These panels offered a starting point for the one off story Terror Tube. Mills and O’Neill were intrigued in particular by the possibility of creating different worlds, of the look, feel and setting of a story changing regularly. Implied here are forms of improvisation, of contrasting forms, of sensorial shocks. This took shape in the form of a new series for 2000AD called Comic Rock, which would tell stories supposedly connected in some form to popular songs. Mills and O’Neill provided the first of these, which was linked to The Jam’s Going Underground, which had been at number 1 a few months earlier. The Comic Rock idea, was for Mills, an opportunity to learn from Metal Hurlant directly. There is a deliberate leaning towards strangeness, towards pushing the boundaries of reader expectations and editorial instruction.

The popularity of the world they created, and the mysterious, unseen character Nemesis, resulted in a two part-sequel, which was followed by the commissioning of a full series. The story focused on Earth in the distant future. This is a future that contains the outmoded, that appears disjointedly non-synchronous. The surface of the planet was a wasteland. Humanity had retreated within the Earth itself, carving out vast subterranean tunnels and caverns. Humanity had also regressed into a state of fear, prejudice, intolerance and superstition, while focusing their irrational fears upon the other, the impure and unclean. In short, the alien.

Throughout Book 1, Mills and O’Neill test the boundaries of the episodic comic form. The structuring of narrative episodes in Book 1 is unconventional for its context in a British anthology comic in the early 80s. The first two episodes are concerned with the slaughter of innocent aliens, and the return of Torquemada, who was believed dead but now exists as a phantom, capable of possessing bodies. This is followed by a three issue narrative arc focusing on a small human community on a remote planet who discover Nemesis, injured and apparently helpless after he is shot down in his craft, the Blitzsphere.

He is captured, offering no resistance, beaten, humiliated and hanged by the locals who hope to receive a reward. The story unfolds with mysterious and gruesome deaths befalling the villagers who captured Nemesis, playing out as an unsettling gothic western.

The next issue offers another jolt, a convulsive shift in setting. We are in the tunnels of Termight,where we are introduced to Purity Brown, one of the rare female characters in 2000AD at the time. She and a bizarre looking human called Googly, are running for their lives, pursued by Terminators. They run down vertical surfaces, and cross the void that intersects two huge subterranean cities - Mausoleum and Necropolis. The two cities meet as opposing mirrored spires. Skyscrapers have evolved into stalactites, with little regard for gravity. These panels play with vertiginous and confusing spaces, inverting the everyday life of Termight.

Then we have an entire week’s storyline relating a meeting between Nemesis and his Great Uncle Baal, an old sorcerer who has been banished to a remote fringe world for his unethical experiments on humans. This is a realm of magic. Not the superstition of the Terminators, but genuine magic, dark, chaotic.

After this, Book 1 follows a more conventional, action orientated path. As the popularity of each issue and story was measured by readers’ polls, it is likely that the focus on action that follows is due to editorial pressure. However, while it may be more conventional in the orientation towards violence and action, the rest of Book 1 is determined by an unusual temporality. Over 9 issues, the story focuses on the Feast of Zamarkand, the most important date in the ritualistic Termight calender, and the occasion for the ritual execution of their political prisoners. The executions of aliens and traitors are therefore of great symbolic importance, and their escape is of great importance to Nemesis due to its potential symbolic value. He hopes that news of a mass escape will rally neutral planets towards resistance against Termight’s murderous empire. But the setting of the Feast of Zamarkand also gives Mills and O’Neill license to develop the extreme and intoxicating strangeness of Termight. As the ceremony begins, a panel shows a procession of terminators. It is a twisted vision of a Spanish Samanta Santa procession, of brotherhoods in their penitential robes and hoods.

The Temple of Terminus is the most bizarre element in all of this, a nightmarish underworld. It is hellish. Architecture becomes figurative. Towering over the scene, emerging from flames and smoke, the spectre of Torquemada. Thanks to a spell cast by Nemesis, the flames of execution are transformed into a dimensional portal, allowing the prisoners to escape.

The architecture, if we can call it that, seems increasingly visceral. Torquemada, inhabiting the bodies of recently dead terminators, also becomes more grotesque.

Book 1 was shocking and innovative, turning the world of future humans into something hellish, casting humanity as demonic. It also established a solid connection with the theoretical readings of Surrealism offered by Hal Foster in Compulsive Beauty. The satyrical nature of the script, the visual doublings and shocks, the reveling in uncanniness, in distortion and excess, resonate with Fosters readings of Surrealism as compulsive and convulsive repetition, as destabilising, and in terms of unsettling desires. And at the end of Book 1, after Nemesis and the prisoners have escaped to a forbidden and forgotten subterranean level, we see another form of the outmoded and non-synchronous, identified as the ruins of Waterloo station, a relic from a long forgotten era. The relationship to Surrealism established by Mills and O’Neill can also be looked at through Walter Benjamin’s 1929 essay, Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia. In his text, he develops the term ‘profane illumination’. This is a perceptual transformation of the everyday into the uncanny and irrational. What is of particular interest here is the correlation to estrangement, to disorientation, defamiliarisation. In particular, profane illumination shares an affinity with Darko Suvin’s definition of science fiction as the literature of cognitive estrangement.

The difference between Suvin’s Cognitive Estrangement and Benjamin’s Profane Illumination is one of the gap between criticism and action, between interpretation and agency. For Benjamin, this is in terms of a revolutionary potential within surrealism, but perhaps it can be usefully translated into political agency, into actually affecting change in the reader, and the reader affecting change in the world. And what we see play out in Book 1 is a politicized surrealism delivered to a mass audience of young readers.

Books 2 and 3 expand the universe and narrative possibilities of Nemesis the Warlock.

For book 2, drawing duties were taken over by Jesus Redondo. The intensity of O’Neill’s approach to drawing had led to deadline problems, whereas Redondo’s far more immediate style was produced at a rate that fitted the weekly schedule. O’Neill returned for Book 3, which is most notable for showing the world of the Warlocks, introducing in particular his baby son Thoth.

And then came book 4, titled The Gothic Empire, which appeared to reinvent the visual and cognitive terrain of Nemesis of the Warlock. But the opening two issues are actually comprised of material that was originally created to be the first parts of Book 1. This was what Mills and O’Neill came up with when first exploring Nemesis as an ongoing series, through a free play of ideas between them, that they describe as jamming, but that might also be thought of as free association, as games of chance, a kind of narrative exquisite corpse of imagery and ideas and story fragments.

But these early pages didn’t explain the universe of which they were a part, so they were put to one side until the story had caught up with them.

Although the Gothic Empire had been created by Mills and O’Neill, it was Bryan Talbot who really transformed these ideas into a narrative and carried Book 4 forward into new territory. These pages revel in a collapsed temporality.

The Gothic Empire focuses on an alien civilization who had been listening to Earth’s early radio broadcasts, which had radiated out into deep space. They recreate the British Empire in extreme detail, fixing their society upon a translated form of Victorian and Edwardian elements. Their own bodies are also transformed, as these aliens have the ability to modify their outward forms, to make themselves look almost human, to the extent that they consider themselves to be human.

They are now at war with the Termight Empire, fighting for survival, never expecting that they would be considered alien and be attacked. The introduction of a these historical periods brings the future universe of Nemesis into a temporal intimacy with surrealism.

We see the obsolescence of the Victorian. The bourgeois remnants of nineteenth century culture.

There is a tension between old and new brought out by the members of The Hellfire Club, a secret society who intend to overthrow the old regime in favour of progress, fashion and reform, who base their ideas on broadcasts from Earth later in the C20.

Talbot’s imagery grows out of the worlds created by Grandville, a significant point of reference for Surrealists and for Walter Benjamin,

He also pays homage to the proto science fiction of Albert Robida, while the use elaborate hatching and tone suggest something of an engraved feel.

The outmoded forms of illustration evoked are reminiscent of the collage narratives of Ernst, as are the qualities of uncanniness present in Talbot’s work on The Gothic Empire. Talbot continued working on Nemesis, producing some arresting imagery for Books 5 and 6, but book 7, which began in October 1987, introduced the work of John Hicklenton. He managed to follow O’Neill and Talbot with something unfamiliar, while somehow remaining consistent with what Mills had started at the beginning of the decade, with the unstable strangeness that lay at the core of these stories.

Book 7, is set in 15th Century Spain. Thoth, the son of Nemesis, is travelling through time, killing all of the earlier incarnations of Torquemada, including Hitler, General Custer and Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder General. He has arrived in Spain to kill the original Thomas de Torquemada, the Grand Inquisitor. As a result of these assassinations, Torquemada, who now has a permanent body, has started to decay, to rot like a living corpse. The present is taken apart by removing pieces of history. Hicklenton offers another take on the outmoded and contamination. He gives us a glimpse of the past, contaminated by the evil of the future, which of course is just a mere reflection of extant religious authority and fanaticism.

He also imbues Nemesis himself with a genuine sense of strangeness and alterity.

Hicklenton’s work on this period of Nemesis revitalised the strip while sustaining its core ideas. The narrative setting in the past also expands the non synchronous, the conflation of unstable temporalities that had been present in the strip from its early stages.

The surrealist interest in the non-synchronous is addressed by Hal Foster through a reading of Ernst Bloch, and his work Heritage of Our Times. Foster cites Bloch’s discussion of the outmoded, and its contamination by fascist exploitation. The idea of a Now is an inconsistent now. There is no shared universal sense of Now. This is the essential factor of the nonsynchronous.

Bloch warns against an incomplete past being exploited by fascism. He interprets Fascism as praying on the fractioning of class, seducing with a mystique of participation and primitivism. It is an appeal to the archaic. Surrealism offers a counterforce to this, a reclaiming of the non-synchronous. In a parallel operation, Nemesis the Warlock does just this, using the nonsynchronous to destabilise the illusion of a constant and unchanging present. It also shows readers what is at stake, giving us the brutal exploitation and violence of the Termight Empire, itself embodying values uncomfortably familiar to readers. Non-synchronous temporality becomes a repository of possibilities, what is to be redeemed as well as what is to be avoided.

Nemesis the Warlock is constructed as entertainment, but also as political education.

We have explicit critiques of imperialism, of intolerance and racism, of religious fundamentalism and dogma. There is a resistance to authority, to normative forms, a celebration of revolutionary energy that is not just about intoxicating the audience, but is itself subtly transformative. And if we return to Walter Benjamin’s essay on Surrealism, he asks how can surrealist experiments be more than mere intoxication, how can they avoid becoming just mystical and reactionary, forms of play that idealise the irrational, taking away the potential for a politics within surrealism.

To end, I’ll try to answer this question. Within the Surrealist currents that circulate through the pages of Nemesis the Warlock, there is a reconfiguring of the limitations addressed by Benjamin. Surrealism’s boundaries were far too limited for Benjamin. It was contained within the boundaries of an intelligentsia. The realm of comics, particularly a comic as popular as 2000AD was in the 1980s, is not so limited. It is a site of contemplative intoxication perhaps, but not limited to a narrow and bourgeois intelligentsia. It was mass culture for children and young adults. The potential force of political awakening at work was formative and direct, yet exhilarating in its shocking visual and narrative pleasures.

In 1962, the traditional science fiction illustrations were dropped from the cover, opting instead for photographs of featured authors, and then in 1963 it lost cover images completely.

Under Michael Moorcock, who became editor in 1964, not only was there a shift in the direction that the content took, towards the emerging experimental sensibilities of Aldiss Ballard and others. There was also a new graphic sensibility. By the turn of the 60s, this had further evolved into a form that was sensationalist, while retaining a critical edge that displayed borrowings from Pop and Surrealism.

What was happening to the covers on New Worlds also had a parallel in mainstream publishing. Earlier in the 1960s, under the art direction of Germano Facetti, Penguin introduced a new formula of reproducing a work of art on the cover of their Classics, Modern Classics, English Library and Science Fiction series. Upon his appointment as editor of the science fiction series in 1963, it was the suggestion of Brian Aldiss to use surrealist artists.

Here we see James Blish, A Case of Conscience, from 1953. Using a detail from The Eye of Silence (1943-44) by Max Ernst. The Dragon in the Sea, Frank Herbert, had Underwater Garden (1939) by Paul Klee. The Day it Rained Forever, a collection of Ray Bradbury short stories, with a detail from Garden Aeroplane Trap (1935) by Ernst.

Mission of Gravity, an work of ‘hard sf’, by Hal Clement, makes use of a detail from The Doubter (1937) by Yves Tanguy, and Olaf Stapledon’s Sirius, shows In the Land Called Precious Stone by Paul Klee.While the presence of Surrealism is explicitly alluded to by Ballard, and the presence of Surrealism in Ballard’s work has been explored in depth, notably by Jeanette Baxter, the Surrealist worlds of Aldiss have yet to be unpacked to the same extent. His short novel Earthworks (1965) , for example, is composed of an extraordinarily textured surrealist fabric. It begins with the image of a dead man floating across the sea, a spectre that is provided with a rational and materialist explanation, but that continues to haunt the protagonist as a series of neurotically produced visual ruptures in the surface of reality. The cadaver breaks up any remaining semblance of normativity that might sustain the psychic landscape, which is reflected in the breakdown of social and political order described in the near-future setting of the novel. Aldiss is as much a builder of surrealist tainted worlds as Ballard, with perhaps an even greater sense of the visual, and a recognition of the need to make the correlations explicit. His recognition of the importance of aligning science fiction with Surrealism was more than a cynical marketing strategy. It was an important part of manifesting the psychically and socially unstable terrain explored in science fiction.

The visual cultures of science fiction would continue to change. The use of Surrealist images in Britain gave way to a greater synthesis of elements in the generation of new imagery in line with pop-culture tendencies, with a convergence between book covers and album covers.

The diffusion of surrealist tendencies was, of course, part of this broader set of trends. Covers such as this for Ballard’s The Wind from Nowhere, by Alan Aldridge, replaced appropriation with synthesis, modernist surrealism with a 60s graphic sensibility. We can see the emergence of new visual possibilities for science fiction.

In creating the universe of Nemesis the Warlock, Mills and O’Neill tapped into the current of Surrealism than ran through the emerging visual culture of science fiction.

In creating the universe of Nemesis the Warlock, Mills and O’Neill tapped into the current of Surrealism than ran through the emerging visual culture of science fiction.It is clear that French comics, and Metal Hurlant in particular had an enormous influence on Mills, that ran parallel in his scripts with his translation of the dark and ambivalent tendencies of the New Wave of British Science Fiction. The roots of Nemesis the Warlock c an be found in the final episodes of the series Ro-Busters. These panels offered a starting point for the one off story Terror Tube. Mills and O’Neill were intrigued in particular by the possibility of creating different worlds, of the look, feel and setting of a story changing regularly. Implied here are forms of improvisation, of contrasting forms, of sensorial shocks. This took shape in the form of a new series for 2000AD called Comic Rock, which would tell stories supposedly connected in some form to popular songs. Mills and O’Neill provided the first of these, which was linked to The Jam’s Going Underground, which had been at number 1 a few months earlier. The Comic Rock idea, was for Mills, an opportunity to learn from Metal Hurlant directly. There is a deliberate leaning towards strangeness, towards pushing the boundaries of reader expectations and editorial instruction.

The popularity of the world they created, and the mysterious, unseen character Nemesis, resulted in a two part-sequel, which was followed by the commissioning of a full series. The story focused on Earth in the distant future. This is a future that contains the outmoded, that appears disjointedly non-synchronous. The surface of the planet was a wasteland. Humanity had retreated within the Earth itself, carving out vast subterranean tunnels and caverns. Humanity had also regressed into a state of fear, prejudice, intolerance and superstition, while focusing their irrational fears upon the other, the impure and unclean. In short, the alien.

The Earth, renamed Termight, was ruled by masked fanatics known as Terminators, under the leadership of Torquemada. Nemesis led the resistance against this genocidal regime, which was dedicated to stamping out all alien life in the galaxy.

Throughout Book 1, Mills and O’Neill test the boundaries of the episodic comic form. The structuring of narrative episodes in Book 1 is unconventional for its context in a British anthology comic in the early 80s. The first two episodes are concerned with the slaughter of innocent aliens, and the return of Torquemada, who was believed dead but now exists as a phantom, capable of possessing bodies. This is followed by a three issue narrative arc focusing on a small human community on a remote planet who discover Nemesis, injured and apparently helpless after he is shot down in his craft, the Blitzsphere.

He is captured, offering no resistance, beaten, humiliated and hanged by the locals who hope to receive a reward. The story unfolds with mysterious and gruesome deaths befalling the villagers who captured Nemesis, playing out as an unsettling gothic western.

The next issue offers another jolt, a convulsive shift in setting. We are in the tunnels of Termight,where we are introduced to Purity Brown, one of the rare female characters in 2000AD at the time. She and a bizarre looking human called Googly, are running for their lives, pursued by Terminators. They run down vertical surfaces, and cross the void that intersects two huge subterranean cities - Mausoleum and Necropolis. The two cities meet as opposing mirrored spires. Skyscrapers have evolved into stalactites, with little regard for gravity. These panels play with vertiginous and confusing spaces, inverting the everyday life of Termight.

Then we have an entire week’s storyline relating a meeting between Nemesis and his Great Uncle Baal, an old sorcerer who has been banished to a remote fringe world for his unethical experiments on humans. This is a realm of magic. Not the superstition of the Terminators, but genuine magic, dark, chaotic.

After this, Book 1 follows a more conventional, action orientated path. As the popularity of each issue and story was measured by readers’ polls, it is likely that the focus on action that follows is due to editorial pressure. However, while it may be more conventional in the orientation towards violence and action, the rest of Book 1 is determined by an unusual temporality. Over 9 issues, the story focuses on the Feast of Zamarkand, the most important date in the ritualistic Termight calender, and the occasion for the ritual execution of their political prisoners. The executions of aliens and traitors are therefore of great symbolic importance, and their escape is of great importance to Nemesis due to its potential symbolic value. He hopes that news of a mass escape will rally neutral planets towards resistance against Termight’s murderous empire. But the setting of the Feast of Zamarkand also gives Mills and O’Neill license to develop the extreme and intoxicating strangeness of Termight. As the ceremony begins, a panel shows a procession of terminators. It is a twisted vision of a Spanish Samanta Santa procession, of brotherhoods in their penitential robes and hoods.

The Temple of Terminus is the most bizarre element in all of this, a nightmarish underworld. It is hellish. Architecture becomes figurative. Towering over the scene, emerging from flames and smoke, the spectre of Torquemada. Thanks to a spell cast by Nemesis, the flames of execution are transformed into a dimensional portal, allowing the prisoners to escape.

The architecture, if we can call it that, seems increasingly visceral. Torquemada, inhabiting the bodies of recently dead terminators, also becomes more grotesque.

Book 1 was shocking and innovative, turning the world of future humans into something hellish, casting humanity as demonic. It also established a solid connection with the theoretical readings of Surrealism offered by Hal Foster in Compulsive Beauty. The satyrical nature of the script, the visual doublings and shocks, the reveling in uncanniness, in distortion and excess, resonate with Fosters readings of Surrealism as compulsive and convulsive repetition, as destabilising, and in terms of unsettling desires. And at the end of Book 1, after Nemesis and the prisoners have escaped to a forbidden and forgotten subterranean level, we see another form of the outmoded and non-synchronous, identified as the ruins of Waterloo station, a relic from a long forgotten era. The relationship to Surrealism established by Mills and O’Neill can also be looked at through Walter Benjamin’s 1929 essay, Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia. In his text, he develops the term ‘profane illumination’. This is a perceptual transformation of the everyday into the uncanny and irrational. What is of particular interest here is the correlation to estrangement, to disorientation, defamiliarisation. In particular, profane illumination shares an affinity with Darko Suvin’s definition of science fiction as the literature of cognitive estrangement.

The difference between Suvin’s Cognitive Estrangement and Benjamin’s Profane Illumination is one of the gap between criticism and action, between interpretation and agency. For Benjamin, this is in terms of a revolutionary potential within surrealism, but perhaps it can be usefully translated into political agency, into actually affecting change in the reader, and the reader affecting change in the world. And what we see play out in Book 1 is a politicized surrealism delivered to a mass audience of young readers.

Books 2 and 3 expand the universe and narrative possibilities of Nemesis the Warlock.

For book 2, drawing duties were taken over by Jesus Redondo. The intensity of O’Neill’s approach to drawing had led to deadline problems, whereas Redondo’s far more immediate style was produced at a rate that fitted the weekly schedule. O’Neill returned for Book 3, which is most notable for showing the world of the Warlocks, introducing in particular his baby son Thoth.

And then came book 4, titled The Gothic Empire, which appeared to reinvent the visual and cognitive terrain of Nemesis of the Warlock. But the opening two issues are actually comprised of material that was originally created to be the first parts of Book 1. This was what Mills and O’Neill came up with when first exploring Nemesis as an ongoing series, through a free play of ideas between them, that they describe as jamming, but that might also be thought of as free association, as games of chance, a kind of narrative exquisite corpse of imagery and ideas and story fragments.

But these early pages didn’t explain the universe of which they were a part, so they were put to one side until the story had caught up with them.

Although the Gothic Empire had been created by Mills and O’Neill, it was Bryan Talbot who really transformed these ideas into a narrative and carried Book 4 forward into new territory. These pages revel in a collapsed temporality.

The Gothic Empire focuses on an alien civilization who had been listening to Earth’s early radio broadcasts, which had radiated out into deep space. They recreate the British Empire in extreme detail, fixing their society upon a translated form of Victorian and Edwardian elements. Their own bodies are also transformed, as these aliens have the ability to modify their outward forms, to make themselves look almost human, to the extent that they consider themselves to be human.

They are now at war with the Termight Empire, fighting for survival, never expecting that they would be considered alien and be attacked. The introduction of a these historical periods brings the future universe of Nemesis into a temporal intimacy with surrealism.

We see the obsolescence of the Victorian. The bourgeois remnants of nineteenth century culture.

There is a tension between old and new brought out by the members of The Hellfire Club, a secret society who intend to overthrow the old regime in favour of progress, fashion and reform, who base their ideas on broadcasts from Earth later in the C20.

Talbot’s imagery grows out of the worlds created by Grandville, a significant point of reference for Surrealists and for Walter Benjamin,

He also pays homage to the proto science fiction of Albert Robida, while the use elaborate hatching and tone suggest something of an engraved feel.

The outmoded forms of illustration evoked are reminiscent of the collage narratives of Ernst, as are the qualities of uncanniness present in Talbot’s work on The Gothic Empire. Talbot continued working on Nemesis, producing some arresting imagery for Books 5 and 6, but book 7, which began in October 1987, introduced the work of John Hicklenton. He managed to follow O’Neill and Talbot with something unfamiliar, while somehow remaining consistent with what Mills had started at the beginning of the decade, with the unstable strangeness that lay at the core of these stories.

Book 7, is set in 15th Century Spain. Thoth, the son of Nemesis, is travelling through time, killing all of the earlier incarnations of Torquemada, including Hitler, General Custer and Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder General. He has arrived in Spain to kill the original Thomas de Torquemada, the Grand Inquisitor. As a result of these assassinations, Torquemada, who now has a permanent body, has started to decay, to rot like a living corpse. The present is taken apart by removing pieces of history. Hicklenton offers another take on the outmoded and contamination. He gives us a glimpse of the past, contaminated by the evil of the future, which of course is just a mere reflection of extant religious authority and fanaticism.

He also imbues Nemesis himself with a genuine sense of strangeness and alterity.

Hicklenton’s work on this period of Nemesis revitalised the strip while sustaining its core ideas. The narrative setting in the past also expands the non synchronous, the conflation of unstable temporalities that had been present in the strip from its early stages.

The surrealist interest in the non-synchronous is addressed by Hal Foster through a reading of Ernst Bloch, and his work Heritage of Our Times. Foster cites Bloch’s discussion of the outmoded, and its contamination by fascist exploitation. The idea of a Now is an inconsistent now. There is no shared universal sense of Now. This is the essential factor of the nonsynchronous.

Bloch warns against an incomplete past being exploited by fascism. He interprets Fascism as praying on the fractioning of class, seducing with a mystique of participation and primitivism. It is an appeal to the archaic. Surrealism offers a counterforce to this, a reclaiming of the non-synchronous. In a parallel operation, Nemesis the Warlock does just this, using the nonsynchronous to destabilise the illusion of a constant and unchanging present. It also shows readers what is at stake, giving us the brutal exploitation and violence of the Termight Empire, itself embodying values uncomfortably familiar to readers. Non-synchronous temporality becomes a repository of possibilities, what is to be redeemed as well as what is to be avoided.

Nemesis the Warlock is constructed as entertainment, but also as political education.

We have explicit critiques of imperialism, of intolerance and racism, of religious fundamentalism and dogma. There is a resistance to authority, to normative forms, a celebration of revolutionary energy that is not just about intoxicating the audience, but is itself subtly transformative. And if we return to Walter Benjamin’s essay on Surrealism, he asks how can surrealist experiments be more than mere intoxication, how can they avoid becoming just mystical and reactionary, forms of play that idealise the irrational, taking away the potential for a politics within surrealism.

To end, I’ll try to answer this question. Within the Surrealist currents that circulate through the pages of Nemesis the Warlock, there is a reconfiguring of the limitations addressed by Benjamin. Surrealism’s boundaries were far too limited for Benjamin. It was contained within the boundaries of an intelligentsia. The realm of comics, particularly a comic as popular as 2000AD was in the 1980s, is not so limited. It is a site of contemplative intoxication perhaps, but not limited to a narrow and bourgeois intelligentsia. It was mass culture for children and young adults. The potential force of political awakening at work was formative and direct, yet exhilarating in its shocking visual and narrative pleasures.